Public Pensions – A Toolkit to Help Actuaries and Others Deceive the Public

ASOP 4 Toolkit: Part 1

It’s the new year and I’ve resolved to start this up again. I welcome disagreement and the calling out of my errors and requests for clarification in the spirit of trying to get things right.

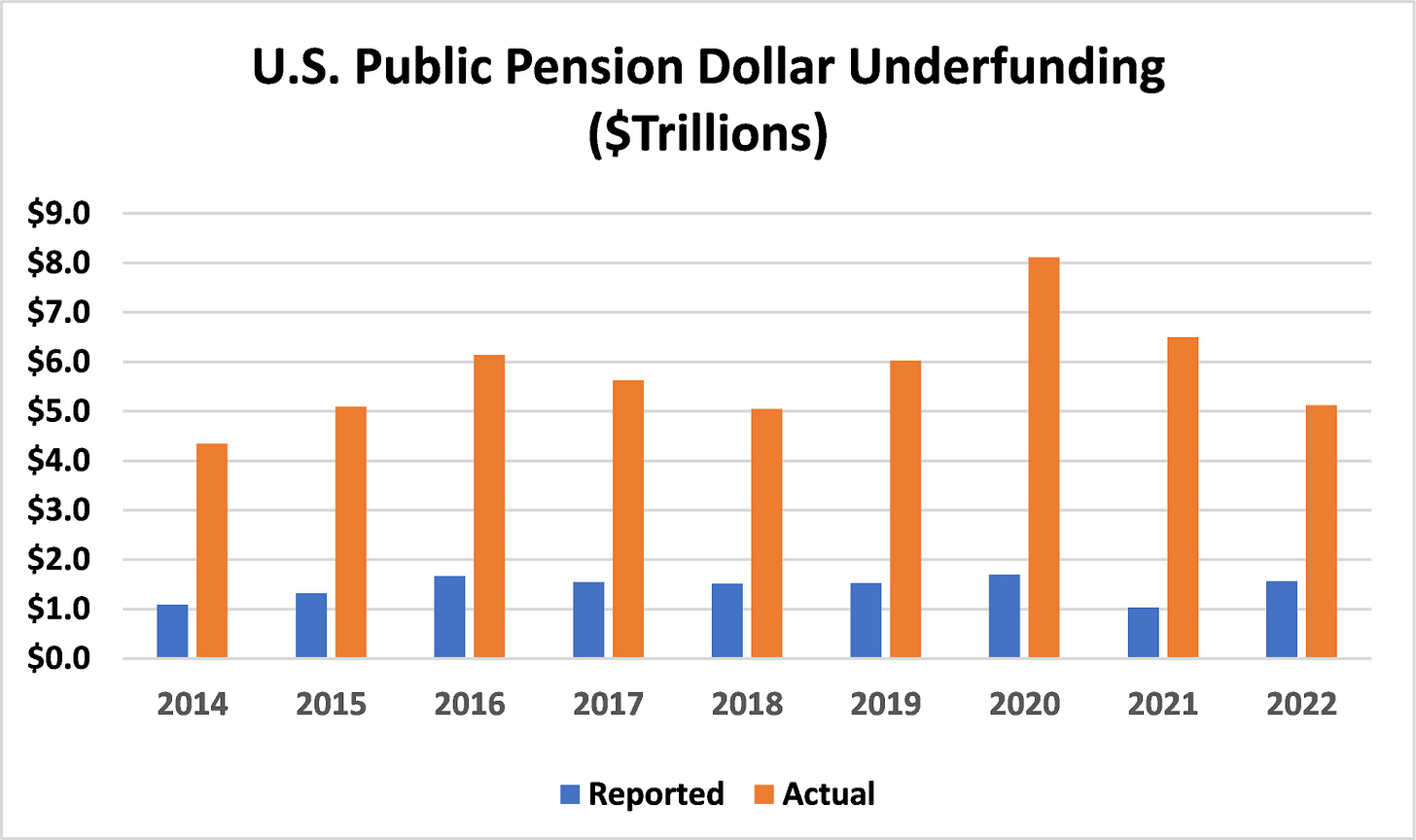

In recent articles in The Opinion Pages and Regulation magazine (Cato), I note that the obligations of public pension plans1 – their “liabilities” – have long been understated by trillions of dollars, which means that unfunded state and local pension debt is likewise understated:

Data Source: Hoover Institution at Stanford University: https://publicpension.stanford.edu/

I express hope that a new disclosure required under actuarial professional standards – Actuarial Standard of Practice No. 4 (ASOP 4) issued by the Actuarial Standards Board (ASB) – will lead to a better understanding of the value of public pension promises.

But I express frustration that a sizeable group of prominent actuaries – who get paid by taxpayers for accurate, good faith, measurements – collaborated with public pension advocacy groups to develop a toolkit to mislead taxpayers and government financial analysts regarding the meaning and implications of the new disclosure.

The above-linked articles have an example to help with the intuition of the finance involved. It shows how actuaries would report $1,292 as the value of an obligation that is worth $2,000, a $708 understatement.

This post critiques the content of the toolkit on the merits. A later post will focus on how we got to this point.

What is a pension “liability”?

Much of the public pension industry’s objection to the new disclosure is based on a misleading conception of “liability.” Consider two alternatives:

Actuarial: The amount of assets that a plan sponsor “expects” will be sufficient to pay earned benefits 50% of the time based on the returns of its investment portfolio that includes risky asset classes with uncertain returns. This liability figure is spoken of conceptually as a “funding target” but it’s used also for financial reporting of government plan sponsors and referenced by most who analyze public pension health.

Finance-Consistent: Based on fundamental principles of finance, this measure is the present value of the contractual promise to pay earned benefits in the future. It is also the total amount that economically rational plan participants should be willing to accept in exchange for giving up their contractual rights to future payments, or the amount that an insurer should require to take on the obligation of making the promised payments. In other words, this is the straightforward common-sense definition of value applied to pension obligations.

The consensus among financial economists and non-actuary finance professionals, and even some actuaries, is that the finance-consistent liability is economically meaningful and that actuarial liability is not appropriate for much of anything.

Yet, as noted above, in the public sector, the actuarial concept of liabilities is used for funding calculations and financial reporting. In the private sector, liabilities for ERISA funding, PBGC premiums, and financial reporting aim for the finance-consistent concept (although they miss to varying degrees).

Naturally, the value of non-pension financial instruments traded in markets is quoted based on finance principles.

Many, if not most, public pension actuaries, alone among professionals who measure the value of financial assets or liabilities, insist on the appropriateness of the actuarial concept of liabilities for funding and accounting. Governmental accounting standards currently require the actuarial concept as well, though the relevant standards2 are under “post-implementation review.” Until the new ASOP 4 disclosures start appearing, the only liabilities one will find in actuarial reports or governmental financial statements are consistent with the actuarial concept.3

Therefore, when people speak of a pension plan being X% funded, they’re usually referring to the actuarial concept. What all this means in English, for example, is that a “fully funded” pension plan is “expected” to have sufficient assets to pay off benefits … about 50% of the time.

Referencing the example from the linked articles: If you went to a bank for a large loan, and, on your personal balance sheet on the application, you listed $1,292 (actuarial concept) as your “liability” for an outstanding existing debt of $2,000 (finance-consistent concept), it would be considered fraud. If you call it a “liability” in an actuarial valuation report, you get a happy client, and if you refuse, you probably lose the client.

Why are actuarial-concept liabilities understated?

The understatement results from discounting future pension payments using the “expected return” of the pension investment portfolio, which is higher than the discount rates required under basic finance principles. Based on bond math, high discount rates result in low liabilities (and vice versa). The “expected return” conceptually is usually the 50th percentile geometric average of annual compounded returns, from an assumed distribution of such returns, of an investment portfolio containing lots of risky assets (publicly traded equity, hedge funds, private equity, etc.).

The finance principle for discount rates stems from the “law of one price”4: if one constructs a portfolio of bonds, the payments from which match future pension payments in amount, timing, and default risk, then the liability and the bonds must have the same value. For the liability value to match the bond portfolio value, the pension discount rate must be the implicit discount rate of the matching bond portfolio.5 This bond portfolio is often called the “replicating portfolio.”

What is the new disclosure required by ASOP 4?

Starting with “funding valuation” reports to be issued mostly in 2024, actuaries must disclose a liability measure for each public pension plan more consistent with finance principles than other reported liabilities. Actuaries are also required to explain the measure’s meaning and implications for contributions, funded status, and benefit security. The new measure is called the “low default risk obligation measure” (“LDROM”) because the discount rates used are based on the yields of more-or-less replicating bonds with low default risk.

This leads us to the toolkit.

What is the toolkit and what is its purpose?

The toolkit was put together by an alliance among (1) major public pension advocacy/lobbying groups6 (including their communications teams), (2) executives and actuaries from several large public retirement systems, and (3) a group of prominent public pension actuaries representing essentially every major actuarial firm that services these plans.

The NCPERS7 website explains the toolkit’s purpose as being “to help pension funds communicate the new requirements of ASOP 4, avoid misunderstanding and misuse of the new disclosure, and communicate the benefits of a well-diversified investment portfolio.” It has three parts: (1) a “Fact Sheet” (2) “suggested language for public pension actuarial valuations”, and (3) “a set of frequently asked questions on investment diversification and other important topics.”

So how did they do?

What are the toolkit’s claims and what’s wrong with them?

Toolkit Claims:

“The difference between the plan’s Actuarial Accrued Liability [actuarial concept] and the LDROM [finance-consistent concept] can be thought of as representing the expected taxpayer savings from investing in the plan’s diversified portfolio compared to investing only in high quality bonds”

“The LDROM helps understand the cost of investing in an all-bond portfolio and significantly lowering expected long-term investment returns”

The claim that the difference between the two liability concepts shows savings from investing in risky assets, or the cost of not doing so, is central to the toolkit’s misdirection.

The toolkit states that LDROM represents “what the [actuarial] liability measurement would be if the plan were to adopt an all-bond investment strategy,” which is true. If one invests in the bonds used to determine the finance-consistent discount rate, then the actuarial discount rate – the expected return of the portfolio – equals the finance-consistent discount rate, and the actuarial liability equals the finance-consistent liability.

The premise here is that the actuarial liability means the “cost” of earned benefits. If that’s true, then the more aggressively one invests, the lower that cost becomes.

The premise is wrong, however. The finance-consistent liability - not the actuarial liability - is the value (or cost) of earned benefits. It is the same regardless of how assets are invested (or how much is contributed). There is no savings to be had by investing more aggressively. The finance-consistent liability (or cost or value) depends on the characteristics of the promised payments, not the investments in the trust.

The difference between the two liability measures represents previously hidden costs. Those hidden costs are for services received by the current or past generations of taxpayers, and they are being shifted to future generations of taxpayers, creating an intergenerational inequity.

A brief digression: wrong thinking about intergenerational equity

Suppose actuarial liabilities are funded and invested aggressively by the current generation of taxpayers, and that the investments return so much that the future generation of taxpayers need not fund anything additional to pay for the costs incurred by the earlier generation. Suppose, further, that there are even funds left over to put toward the future generation’s pension costs for the services they receive.

One sometimes-heard description of this result is that it reflects intergenerational inequity in benefiting the later generation at the expense of the current generation, who, in hindsight, funded too much, giving the later generation an undeserved windfall.

But that framing is wrong. By funding less than the cost (the finance-consistent liability), the current generation transfers some of the cost to the later generation. Even though the later generation gets to contribute to the trust less than the pension costs they incurred, they will have been insufficiently rewarded for the obligation and risk foisted upon them by the current generation. The market would have rewarded the later generation even more for bearing the same cost and risk outside of a pension plan. Some of that reward is instead taken by the current generation in the form of funding less than their cost.

In practice, public pension plans are mechanisms that allow earlier generations of taxpayers to stealthily impose on future generations the costs for some of the services received by the earlier generations.

The toolkit’s logic leads to the conclusion that diversification is bad

Taking the toolkit’s argument to its logical conclusion, the plan should invest 100% of the pension trust portfolio in the riskiest asset with the highest “expected return.” That would maximize the claimed “expected taxpayer savings” and decrease the “cost” vs. investing in “the plan’s diversified portfolio.” Under the toolkit’s logic, diversification is bad, and the more risk, the better.

Finance teaches that liabilities are not first-order dependent on investments

Again, for liabilities based on finance principles, investments are essentially irrelevant. Whether one invests 100% of the assets in the riskiest asset, or the replicating bond portfolio (that fully hedges the liability), or even if there are no assets at all, the liability is the same if the amounts, timing, and default risk of future payments are the same. (Of course, having no assets might increase the default risk on the margin, creating a second-order effect.)

Toolkit Claims:

“LDROM is not a measure of public pension plan funding”; and relatedly

“LDROM is not a measure of pension plan health”; and

“LDROM is not the ‘true measure’ of public pension liabilities”

The toolkit explains:

For many years some financial economists have claimed public pension plans are understating the value of the pension promise by not using discount rates similar to those required for the LDROM. This new disclosure requirement will likely lead to a resurgence of such claims.

Well, the toolkit got that right, except that financial economists are essentially unanimous, and it neglects to mention that the claim is based on sound economic reasoning. It continues:

To counter this risk of misrepresentation [by financial economists], the ASB specifically states that ‘The calculation and disclosure of this additional measure [the LDROM] is not intended to suggest that this is the “right” liability measure for a pension plan.’

That the finance-consistent liability is not the “right” or “true” liability is one of the public pension actuarial industry’s favorite tropes. The implied logic is that since LDROM isn’t the “right” definition according to the ASB, the actuarial definition must be fine (even “right”). But the ASB did not say that. By adding the LDROM requirement, the ASB is implicitly saying that the actuarial-concept liability is also not the “right” definition.

In fact, the ASB states, in the sentence that immediately follows the one highlighted above:

However, the ASB does believe that this additional disclosure provides a more complete assessment of a plan’s funded status and provides additional information regarding the security of benefits that members have earned as of the measurement date.

The toolkit uses one ASB statement to justify downplaying LDROM, but ignores the statement that directly contradicts its claim that LDROM does not indicate funding levels.

The ASB, in requiring the new disclosure, is deeming it unprofessional to base a funding calculation on the actuarial definition of liabilities without also acknowledging the finance-consistent definition.

An honest, accurate explanation of the type the ASB likely had in mind is that LDROM, a finance-consistent liability,8 is the sponsor’s pension debt, properly understood, and the difference between the finance-consistent and actuarial liabilities is previously hidden debt. Because the plan is less well funded on the finance-consistent liability basis, benefits are less secure than indicated by other liability measures. The actual pension debt is not as well collateralized as otherwise implied.

But regardless of what the ASB does or doesn’t say regarding “right” measures, the LDROM is at least somewhat economically meaningful, and the currently reported actuarial liability is not.

Toolkit Claim: “The LDROM may be used to mislead stakeholders, including workers, policymakers, and taxpayers about the financial health of a pension plan”

This is advanced-level irony.

In fact, LDROM is the least misleading liability measure one will soon see in an actuarial report.

Conclusion: Beware of actuaries bearing disclosures

The toolkit seems part of an attempt to get as much of the public pension industry as possible singing from the same propagandistic hymn sheet to misdirect attention away from the new disclosure. In NCPERS’s toolkit rollout webcast, one can hear the speakers’ concern about the consequences of the LDROM possibly getting attention. The webcast is effectively a strategy session about how best to spin the meaning of the LDROM to the industry’s advantage and/or downplay it, and how the toolkit can be used to help accomplish that.

If you read a disclosure with explanatory language similar or identical to the toolkit’s, don’t be fooled. Focus instead on the difference between the LDROM and the liability reported elsewhere as a start to understanding how much worse plan funding is and how much higher the sponsor’s debt is than you probably realized.

Preview of next post

Why wouldn’t actuaries simply use the new disclosure requirement as an opportunity to educate their clients and the public by providing honest objective measurements and explanations? Why have so many prominent actuaries instead conspired with special interest lobbying organizations, which exist to advance one-sided political points of view, to mislead and misdirect? Why do these groups treat as political adversaries those who advocate the application of basic finance principles to some of the largest financial programs in the world? My next post will attempt to address some of this.

“Public pension plans” refer to the traditional pension plans sponsored by state and local governments in the U.S. for their employees.

GASB Statements 67 and 68. GASB stands for Governmental Accounting Standards Board, which sets accounting standards for the government entities that sponsor these plans.

For about ten years, through 2013, New York City pension plan actuarial reports included, as a disclosure only, liabilities based on finance principles. After the actuary during those years, Robert North, retired, his successor discontinued the practice. With the new ASOP 4 disclosure, something similar will have to be added back.

A condition that eliminates the possibility for riskless arbitrage

In practice, one would likely use a discount curve where future payments at different times have different discount rates, reflecting the market “term structure” of interest rates.

NCPERS (National Conference on Public Employee Retirement Systems), NASRA (National Association of State Retirement Administrators), NCTR (National Council on Teacher Retirement), NIRS (National Institute on Retirement Security). The GFOA (Government Finance Officers Association) has formally endorsed the toolkit as well.

They describe themselves as follows: “ … the largest trade association for public pensions, representing approximately 500 plans, plan sponsors, and other stakeholders throughout the United States and Canada…. we are a unique network of trustees, administrators, public officials, and investment professionals who collectively oversee approximately $4 trillion in retirement funds managed on behalf of seven million retirees and nearly 15 million active public servants — including firefighters, law enforcement officers, teachers, and other public servants. Founded in 1941, NCPERS is the principal trade association working to promote and protect pensions by focusing on Advocacy, Research and Education for the benefit of public sector pension stakeholders…It’s who we ARE!”

I’m intentionally glossing over so-called actuarial “funding methods” which is a potential difference between the LDROM and actuarial liabilities in addition to discount rates. Addressing that would make this exposition much more complicated without adding much. If I get a lot of pushback from actuaries (or others), I may address it separately in a later post.

Actuaries claiming that LDROM difference with the "official" measurement represents a "savings" had better watch out.

I do have an alternative interpretation of the difference that they're really not going to enjoy. I'm just waiting for one of them to actually go live with one of these explanations.